A United Front or A Divisive Industrial Policy?

In the wake of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the vulnerability of European skies to modern aerial threats—from cruise missiles and ballistic missiles to swarms of low-cost drones—became starkly apparent. Out of this urgent reassessment, the German-led European Sky Shield Initiative (ESSI) was born in late 2022.1 Hailed by its proponents as a landmark step towards a united, protected continent, it has also drawn sharp criticism, revealing divisions about the future of European defense.2 Is ESSI the pragmatic united front Europe needs, or is it a thinly veiled industrial policy that risks fracturing the very unity it claims to build?

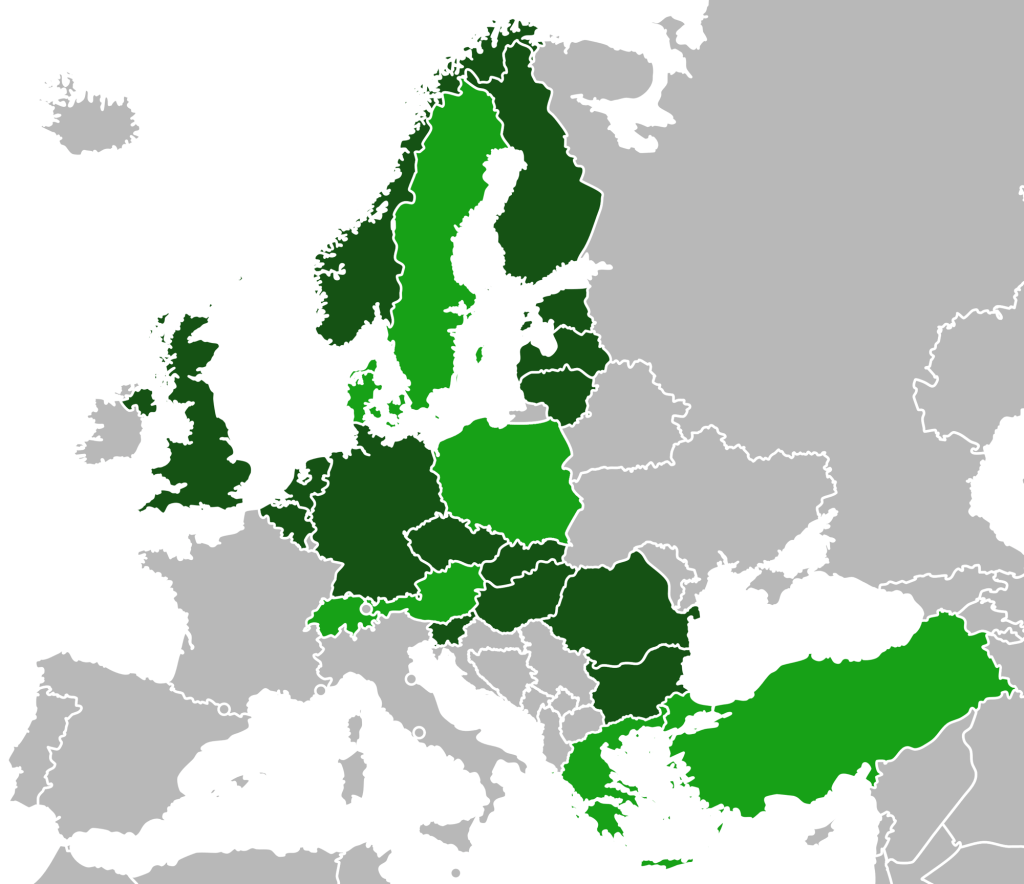

Member States of European Sky Shield Initiative. Dark green (founding members in 2022),

light green (joined members in 2023 and 2024.

What is the European Sky Shield Initiative?

At its core, ESSI is a cooperative procurement project.3 The initiative aims to create a multi-layered, integrated air and missile defense system across the continent by streamlining the acquisition of proven, off-the-shelf systems.4 The architecture is envisioned in three layers:

Medium-range: Centered on the German-made 5IRIS−T SLM, a system that has earned significant acclaim for its performance in Ukraine.6

Long-range: Covered by the American-made MIM-104 Patriot system, the long-standing backbone of many NATO allies’ air defense.

Exo-atmospheric: The highest layer, designed to intercept ballistic missiles, would be handled by the Israeli-American Arrow 3 system.7

As of mid-2025, the initiative has garnered the support of over 20 European nations, including the United Kingdom, the Nordic countries, and Eastern European states.8 The logic is compelling: by purchasing systems collectively, nations can reduce costs, speed up delivery, and ensure seamless interoperability from day one.9It is a pragmatic solution to a pressing problem.

The “United Front” Argument: Pragmatism in the Face of Threat

Supporters of ESSI argue that speed and effectiveness are paramount. The war in Ukraine demonstrated that waiting for bespoke, pan-European defense projects to mature over decades is a luxury Europe can no longer afford.

1. Addressing Urgent Gaps: Most European nations have glaring deficiencies in their air defense capabilities, particularly against ballistic missiles.10 ESSI offers a direct and rapid path to plugging these gaps with battle-tested systems.

2. Cost Efficiency: Joint procurement on this scale promises significant cost savings, making advanced systems like Arrow 3 accessible to smaller nations that could never afford them alone.

3. NATO Interoperability: By standardizing on systems like the Patriot, ESSI reinforces NATO’s Integrated Air and Missile Defence (IAMD).11 It creates a more coherent and legible operational picture for military commanders, simplifying command and control across a vast geographical area.

From this perspective, ESSI is the epitome of smart defense—a rational, collaborative effort to secure European citizens under a common, interoperable shield.

The “Industrial Policy” Critique: A Blow to European Sovereignty?

However, the initiative has notable objectors, chief among them France, with Italy and Poland also remaining on the outside. Their critique is not just about which systems are chosen, but where they come from. The core of the argument is that ESSI, in its current form, actively undermines Europe’s long-term goal of achieving “strategic autonomy.”

The primary grievance is the heavy reliance on American and Israeli technology.12 France, in particular, points to its own advanced, domestically produced alternative to the Patriot system: the SAMP/T “Mamba,” developed with Italy.13 Proponents of a sovereign European approach argue that by purchasing non-European systems, ESSI:

Sidelines European Industry: It funnels billions of European taxpayer euros to American and Israeli defense contractors, starving European champions like MBDA France and Thales of the funds needed for research and development. This weakens the European Defense Technological and Industrial Base (EDTIB), a key pillar of strategic autonomy.

Creates Political Dependencies: The use of systems like Patriot and Arrow 3 is subject to approval from Washington D.C. This gives the United States a potential veto over aspects of European security. In a world of shifting geopolitical tides, critics ask if Europe can truly afford to have its defense capabilities dependent on the political whims of a non-European ally.

Neglects the French Vision: France has long championed a different path—one centered on developing, producing, and procuring European systems to ensure the continent’s freedom of action. This vision is embodied in the ongoing development of the next-generation SAMP/T NG. By endorsing ESSI, European nations are, in effect, rejecting this vision of a sovereign defense identity.

A Continent Divided on its Future

The clash between ESSI and the French-led alternative is more than a simple procurement debate; it is a battle for the soul of European defense.

On one side, you have the German-led pragmatists who see an immediate threat and an immediate, off-the-shelf solution. For them, interoperability with the US and within NATO is the ultimate priority. The industrial fallout is a secondary concern compared to the urgency of the security situation.

On the other side, you have the French-led strategic purists who argue that short-term solutions should not come at the cost of long-term independence. For them, building a sovereign European defense industry is not a matter of economic protectionism, but a fundamental prerequisite for Europe to act as a credible, independent geopolitical actor.

Conclusion: A Shield with Cracks?

The European Sky Shield Initiative has successfully galvanized a continent into confronting its air defense vulnerabilities. It has forced a critical and long-overdue conversation. However, in its pursuit of a quick and interoperable fix, it has prioritized transatlantic cohesion over European industrial sovereignty, creating a significant strategic and political rift.

The initiative risks creating a two-tiered Europe: one group of nations deeply integrated into a US-centric security architecture, and another striving for an independent defense capability. As we move forward, the question for European leaders is whether these two visions can coexist and eventually converge. Can a future iteration of ESSI incorporate sovereign European systems like the SAMP/T NG? Or will the continent remain divided, protected by a shield that, while strong in some places, is weakened by the political and industrial cracks running through it? The security of Europe may depend on finding the right balance between immediate protection and long-term self-reliance.

List of sources

- German-led European Sky Shield Initiative (ESSI) born in late 2022.

- ESSI has drawn criticism, revealing divisions about the future of European defense.

- ESSI is a cooperative procurement project.

- The initiative aims to create a multi-layered, integrated air and missile defense system across the continent by streamlining the acquisition of proven, off-the-shelf systems.

- Medium-range layer centered on the German-made IRIS-T SLM.

- IRIS-T SLM has earned significant acclaim for its performance in Ukraine.

- Exo-atmospheric layer would be handled by the Israeli-American Arrow 3 system.

- As of mid-2025, the initiative has garnered the support of over 20 European nations, including the United Kingdom, the Nordic countries, and Eastern European states.

- By purchasing systems collectively, nations can reduce costs, speed up delivery, and ensure seamless interoperability from day one.

- Most European nations have glaring deficiencies in their air defense capabilities, particularly against ballistic missiles.

- By standardizing on systems like the Patriot, ESSI reinforces NATO’s Integrated Air and Missile Defence (IAMD).

- The primary grievance is the heavy reliance on American and Israeli technology.

- France points to its own advanced, domestically produced alternative to the Patriot system: the SAMP/T “Mamba,” developed with Italy.